TL;DR: Some observational studies found a correlation between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and autism. However, correlation isn’t causation. Better-controlled studies show the association disappears when accounting for genetics and maternal health factors. Overall: the evidence doesn’t support a causal link.

Last week, President Donald Trump and Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. urged Americans to avoid Tylenol (acetaminophen) during pregnancy, citing a possible link to autism. News outlets, scientists and commentators rushed to respond, leaving many people unsure what to believe.

Fortunately, autism and its causes have been studied extensively for decades, including research on the potential effects of acetaminophen use during pregnancy At Consensus, our mission is to make it easier to navigate scientific literature and bring clarity to complex questions like this one. So today, we’re using Consensus to dig into the actual studies behind this debate and shed light on whether the concern is supported by evidence.

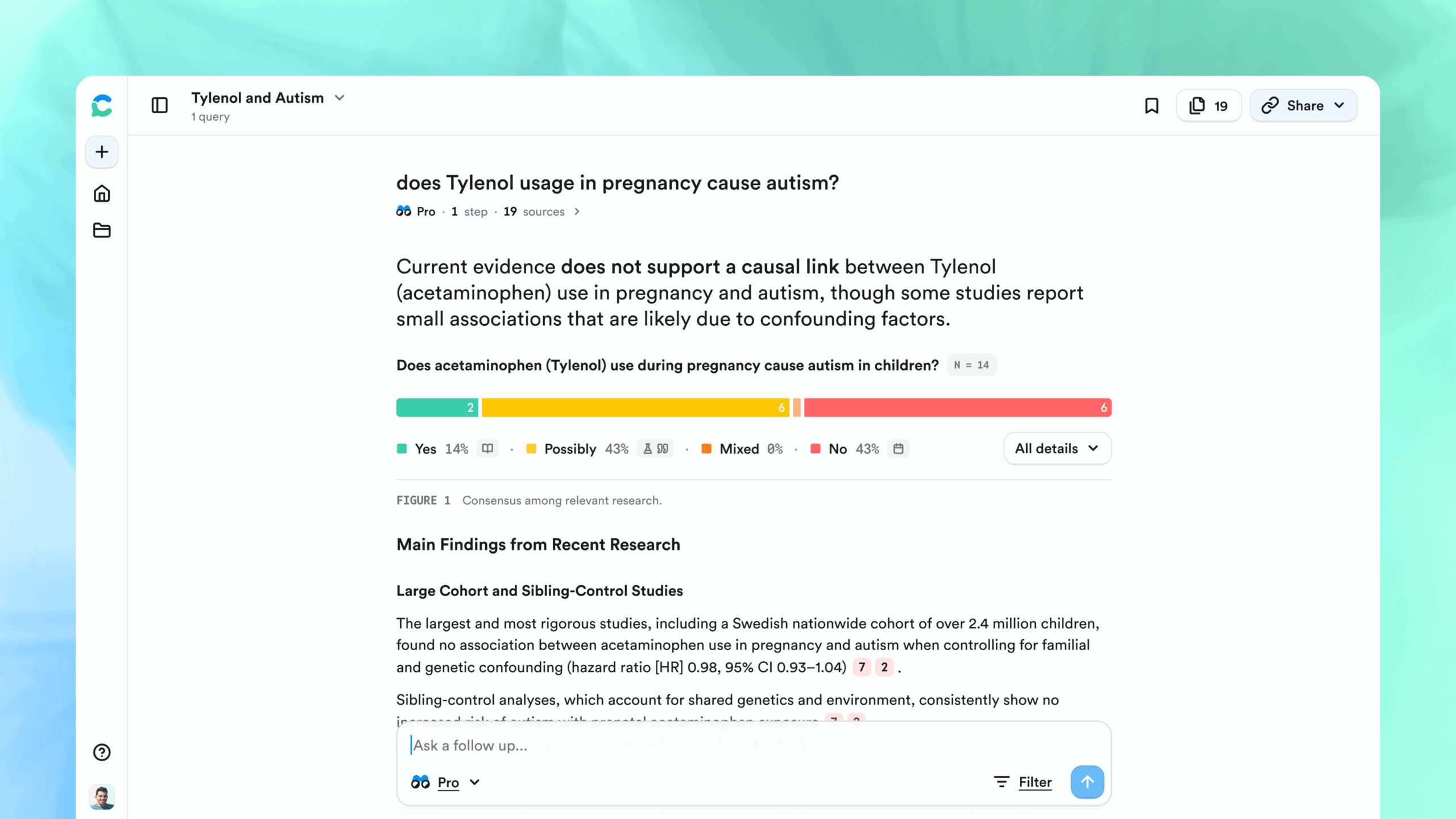

💡 Search Consensus: Does Tylenol usage in pregnancy cause autism?

The Root of the Concern: An Association Between Tylenol Use and Autism

If you look at the Consensus analysis of the research you will immediately see the results are ~mixed with studies on both sides of the debate, This immediately shows something that is important to call out: the statement made by RFK and Trump did not come from nowhere.

Let’s look at a few of the papers that have shown an association:

- S. Alemany et al. (2021): this study looked at 74k different mother-child pairs and found a 19% increased presence of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis in children that had prenatal exposure to acetaminophen. This study showed an association, but like all observational studies, it does not prove causation

- Yuelong Ji et al. (2020): this study looked at 996 mother-child pairs from a single birth cohort and found a 1.6x to 4.1x increased risk of physician-diagnosed ASD for children who had measured umbilical cord acetaminophen exposure. Similarly, this study showed a real association, but does not prove causation.

There are two important takeaways from these papers:

-

Yes, real studies have found an association. These likely informed the recent statements from public figures.

-

But they are only two data points, and they are observational studies, they show correlation, not causation.

Correlation Does Not = Causation

Showing that two variables are associated in an observational study does not mean that one causes the other. Ice cream consumption and shark attacks are correlated. As ice cream consumption increases, so does shark attacks. Obviously, this does not mean that ice cream consumption causes these shark attacks. Instead, there is a third variable causing both outcomes: summer heat.

Showing correlation is noteworthy and is valuable information to dictate where to research further, but it proves very little in and of itself. Let’s take a deeper look at studies that did dig further into this association:

- Z. Liew et al. (2016): this study looked at over 60k mother-child pairs as a part of a Danish birth cohort and found an association between acetaminophen use and ASD with hyperkinetic symptoms, but found no association between acetaminophen and all other types of autism.

- Per Damkier et al. (2024): this systematic review looked across nine independent studies that examined this question and found that all studies that observed a positive association had major limitations, and when controlling for familial and genetic factors the association between autism and acetaminophen disappeared.

- V. H. Ahlqvist et al. (2024): this cohort study looked at over 250k participants and found only a 0.2% net increase in autism in those exposed to acetaminophen during pregnancy. This study concluded there is no meaningful association and that previous studies that found an association were likely attributable to familial cofounding factors.

- C. Andrade et al. (2016): this literature review published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry had very similar conclusions as Damkier (2024): the research showing an association did not do a great job controlling for a variety of factors and the totality of evidence does not support a connection between acetaminophen use in pregnancy and autism

These studies do not definitively prove any one model of acetaminophen and autism. What they do do is cast very serious doubts that the association observed in the previously mentioned studies is casual and worthy of any public concern.

To see even more studies on this subject, try out our comprehensive literature search feature, Deep Search: Does Tylenol usage in pregnancy cause autism?

Overall Takeaway

The research on Tylenol use during pregnancy and autism risk paints a much more nuanced picture than the headlines suggest. It is true that some well-designed studies have found a real, measurable association between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and autism or hyperactivity diagnoses later in childhood. These findings are what fuel statements like the ones made by President Trump and RFK.

But when we zoom out and look at the entire body of research, the story becomes clearer: most large, high-quality studies, especially those that carefully account for genetics and family environment, find little to no meaningful increase in autism risk. The strongest evidence we have today suggests that, if acetaminophen does play a role, the effect is very small and likely limited to certain subgroups (for example, children with co-occurring hyperactivity disorders).

The research is mixed, but the weight of evidence does not support the idea that Tylenol causes autism. Occasional, medically necessary use during pregnancy is still considered safe by major clinical guidelines, though, as always, pregnant individuals should discuss any medication use with their healthcare provider