Check out this answer from Consensus:

While the SPE remains a seminal study in social psychology, its findings have not been rigorously replicated by other researchers. The broader issue of replicability in social science, as highlighted by Camerer et al., underscores the importance of skepticism and rigorous methodology in scientific research1 2. Future efforts should focus on developing ethical and methodologically sound ways to test the core hypotheses of the SPE, ensuring that its conclusions are robust and reliable.

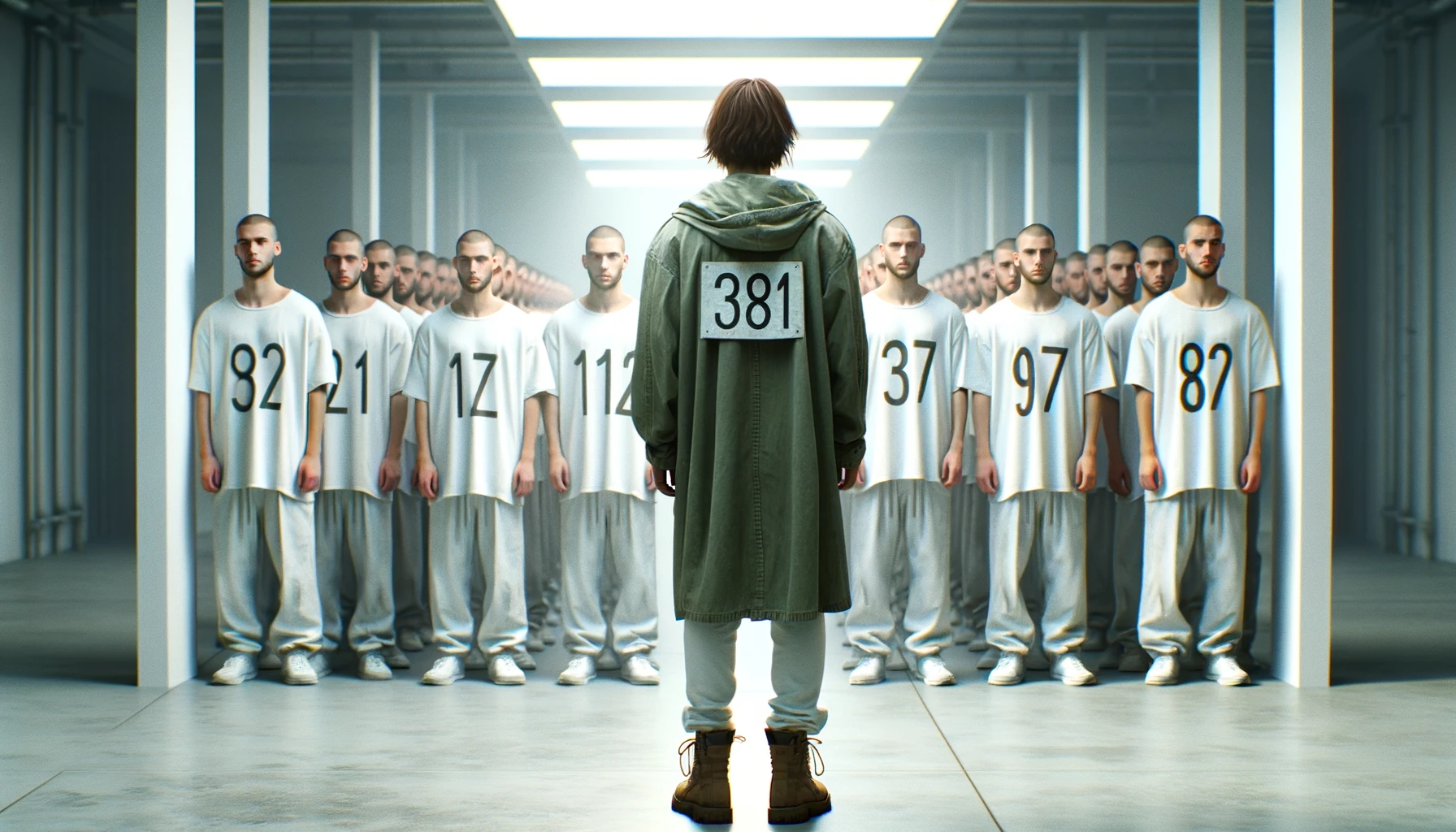

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), conducted by Philip Zimbardo in 1971, is one of the most well-known and controversial studies in social psychology. It aimed to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power by assigning participants to the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison environment. The findings suggested that situational factors, rather than individual personality traits, could lead to abusive behavior. However, the replicability of these results has been a subject of debate. This article explores whether the results of the SPE have been replicated by other researchers.

Replicability in Social Science

Replicability is a cornerstone of scientific research, ensuring that findings are reliable and not due to chance. A study by Camerer et al. examined the replicability of 21 social science experiments published in high-impact journals like Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. They found that 62% of the studies could be successfully replicated, although the effect sizes were generally smaller in the replications1. This highlights the challenges in replicating social science experiments and raises questions about the robustness of classic studies like the SPE.

Revisiting the Stanford Prison Experiment

A case study by researchers revisited the SPE to assess its acceptance and skepticism within the academic community. The study analyzed citations of the SPE in criminology and criminal justice journals from 1975 to 2014. The findings revealed that scholars widely accepted the conclusions of the SPE, even when expressing concerns about its methodology. This uncritical acceptance suggests a need for more rigorous replication efforts and adherence to scientific skepticism2.

Challenges in Replicating the SPE

Several factors make the replication of the SPE particularly challenging:

- Ethical Concerns: The original experiment faced significant ethical criticisms due to the psychological harm experienced by participants. Modern ethical standards would likely prevent a direct replication of the study.

- Contextual Differences: The social and cultural context of the early 1970s may have influenced the behavior of participants in ways that are not replicable today.

- Methodological Issues: The original study lacked rigorous controls and standardized procedures, making it difficult to replicate with precision.

Have results from the Stanford Prison Experiment been replicated by others?

Matthew Grawitch has answered Unlikely

An expert from Saint Louis University in Psychology

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) has been used a one of the “important studies” in psychology. As mentioned in the question, recent evidence suggests what many psychologists believed for quite a while, that perhaps its conclusions were less valid than claimed by researchers. To the best of my knowledge, no researchers have ever been able to replicate the results of the experiment. In addition, Haslam, Reicher, and Van Bavel (in press) have an article coming out that summarizes some of the issues with the “experiment” and focuses on “rethinking the nature of cruelty” (for a more lay oriented write up, see here). In addition, the BBC attempted to replicate the study and was unsuccessful.

While Phillip Zimbardo has released a set of rebuttals to some of the criticisms levied recently against he and the SPE, he doesn’t really address the lack of validity of the study. He does refer to Lovibond, Mithiran, and Adams (1979), which found that more standard custodial regimes produce more authoritarian behavior and more hostility than more participatory regimes. However, a commentary on the article contends that what was found by Lovibond et al. would apply more to a school or hospital setting as opposed to a prison setting.

When considering the evidence, it is unlikely that the SPE is replicable. Furthermore, as a simulation in which individuals were expressly selected to play roles (as opposed to the way prisons actually work), the results of the study – even given all the criticisms – are questionable. The claims made about the study results by Zimbardo himself (in much of his writings on the subject since then) overhype the importance of situational factors in affecting behavior. Yes, some individuals in situations like that, especially when their personality traits are aligned with desires for power and control, will likely behave poorly. Others will experience very different reactions, as Haslam et al. discussed, and only when structures exist to force conformity will individuals go against their natural inclinations and conform (the strength of the power to force conformity must be enough to override individual characteristics that might resist conformity). In the case of SPE, it appears that it was less a function of the individuals “overidentifying” with their roles and choosing to act cruelly as it was a function of the fact that the “leader” (i.e. Zimbardo) exerted enough power to force conformity and manipulate the situation to obtain the outcomes he was looking for (so in that way, it actually probably lends more credence to the work of Stanley Milgram).

The ultimate conclusion here is that people don’t just behave a certain way because of a given role. Their personality traits play a role in their decisions to behave in a given way. Furthermore, those in a position to exert power over someone in a given role can effectively override some individual predispositions, assuming the power is of sufficient magnitude.